On Kahn-Harris' book Extreme Metal - Music and Culture on the Edge

The seeds for this blog were planted upon feeling an urge to reflect on my enduring obsession with extreme metal music in conjunction with other aspect of my life which seemingly contradict this interest. For the last five years or so, I’ve accumulated academic, traveling and personal experiences which have all contributed to make me a bit less self-centered and more appreciative of just how complex the world is, especially when looking beyond metal-archives.com. I befriended people in several Asian countries, became vegan, learned new languages, became a dad, taught music to kids with special needs and became obsessed with books (notably about history). As resistance to politics and change persists in the metal world, I can no longer turn a blind’s eye on “the world” and its problems, nor can I remain the cynical observer that I contented myself in being before. Yet I find myself still obsessed with extreme metal, unable to fully reject the music and its companion lifestyle (I still buy a fair amount of merch!). At the same time, I don’t always feel able to have reflexive conversations about difficult topics that do not relate to metal itself within the scene. Often my musings are confronted with a refusal to let politics (a term too narrowly understood by some people) tarnish a conversation about metal, as if music was a separate entity that doesn’t exist in the real world.

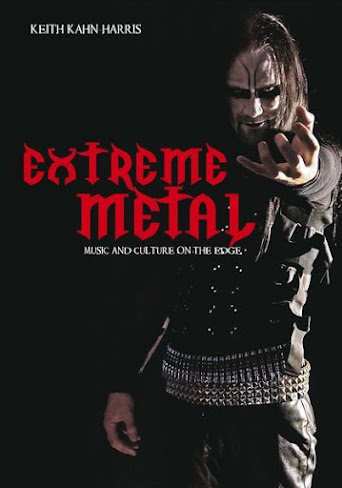

I guess at this point I was fully ripe for some

literature addressing such issues. Fortunately, I found just that in Keith

Kahn-Harris’ book Extreme Metal: Music and Culture on the Edge. I’ve

read a couple books on extreme metal before (most of which were not academic

studies though), but this is by far the best one I’ve encountered. More than an

accumulation of trivial and biographical knowledge about bands, it is a

sociological study that makes a distinction rarely addressed in that very field:

Extreme metal is not the same phenomenon as heavy metal or more mainstream

manifestations of metal music, and therefore requires a different treatment in

analysis than its parent genres. Fans know this already, but rarely does that

notion permeate beyond the scene. The book asks difficult questions about

extreme metal to an extent that can potentially feel threatening to those of us

who identify deeply with the genre. For that very reason, it is in my opinion

an essential read for every lover of extreme metal. Let's look at some of the book's key points.

The demographics of extreme metal are not a simple

coincidence.

Extreme metal remains essentially white. Born out of

American styles of music and developed mostly in Europe and North America, it’s

a kind of music that has gradually stripped itself from its Afro-American

roots. If early bands such as Black Sabbath were essentially heavier blues rock

bands, extreme metal has gradually distanced itself from such genres by taking

its influences directly from metal. As a result, the style of music has evolved

into a highly idiosyncratic one. In the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, nü-metal

emerged as a subgenre of metal born out of very different roots. It fused

hip-hop and funk, Afro-American music genres, into metal and did not adhere to

the dark fantastical aesthetic cultivated within the metal scene. It was, and

still is, perceived as metal done by outsiders, people who did not learn metal

from the classics and who therefore could not legitimately contribute to this

subculture. According to Kahn-Harris, this epitomizes metal’s unconfessed

resistance to black culture, or any foreign musical culture for that

matter. We can counterargue that metal exists nowadays in most countries, that chinese folk metal exists and that several band have built an

orientalist gimmick around foreign religions, but these do not change the

fundamental rudiments to which extreme metal music still latches. If anything, those cases are merely exceptions to the rule. In reality, folk elements in metal act more often as musical embellishment than as something

radically changing the foundations of what metal can be. Nü-metal, with its

bass-heavy emphasis on rhythm, locked grooves, syncopated notes and overall

hip-hop aesthetics was a much more radical proposition than layering foreign

instruments on top of black metal riffs. This helps us understand why metal has

remained a largely white phenomenon, one that frequently “others” different

types of music and thus discourages people from other scenes from engaging with

it. Its musical criteria are heavily defined by metal’s distinction from other

musics, a reflection of how hostile the scene can be to marginalized newcomers. It may all operate at an unconscious level, but it's no reason to be in denial.

There are essentially two types of intangible capital

within the global extreme metal scene. Every metalhead negotiates the two to

get by, albeit in different proportions.

For one, a deep knowledge and commitment to the scene

represents the oldest form of capital within the metal world. The quest for

encyclopedic knowledge of bands or deep involvement in the scene is oriented towards the community and its preservation. Another type of

capital, though, values individualism and differentiation from the collective.

In simpler terms, it refers to the elitism often encountered in underground

networks of extreme metal. The desire to be radically different from the common

metalhead, in musical taste, ideology or otherwise, steadily gained capital

since emergence of 1990’s black metal in Norway. I recognize myself in both,

but especially in the latter. But this individualism that I’ve cultivated goes

further. My penchant musical transgression has slowly overwritten my commitment

to the metal scene, to a point where I’ve been actively looking for extreme

metal music that challenges the very scene from which it emerges. As much as I

diversify my music tastes and expand my world view, a desire to be different

from other metalheads remains at the core of my identity, something rewarded by

what Harris calls “transgressive subcultural capital”.

The extreme metal scene is a safe space.

I’ll never digest Panzerfaust’s T-shirt back

print claiming “this is not a fucking safe space”. It used to bother me

for the blatant depiction of conservatism and attack on social conscience, but

now it just baffles me for its ignorance and lack of reflexivity. Extreme

metal, and especially black metal, are the safest of all safe spaces. Indeed,

it is one of the rare areas of contemporary society where ideas of misogyny,

racism and fascism can be casually articulated without much reprimand or overt

criticism. These ideas were able to gain currency thanks to the quest for

transgression kicked-off by the Norwegian black metal scene almost 30 years ago.

They are now part of the culture of the scene, even when a majority of

metalheads do not support them. One of the main reasons why such ideas have

survived is that they can easily be brushed as comical and unimportant by most

metalheads who do not agree with them. Similarly, people who perpetrate these

ideas in the scene can downplay their importance by walking the fine line

between fantasy and real-life politics. Furthermore, the underground, where

these ideas circulate, is rarely given mainstream media attention which allows

the scene to go on without massive criticism. This lack of attention from a

larger cultural audience makes extreme metal a space where people can engage

with transgression and extremity safely without compromising the mundanity of

their daily lives. This is a form of escapism that provides an alternative to

the real world in which people generally must engage with politics at some

level and face the consequences of their actions. The complex balance of

capital necessary for metalheads to acquire in order to fit in the hierarchy of

the scene makes it all the more difficult to openly challenge harmful ideas.

Looking back at metal’s grey zones and claims of political detachment, it doesn’t really hold up. The idea of music as separated from politics is facilitated by an obsession with autonomous “artworks” or “masterpieces” which are created by “geniuses” predates metal. It's an idea that emerged innineteenth-century Europe, when musical taste became a substitute to monetary capital in efforts to control public access to culture. Such a discourse around autonomous artworks is still prevalent today in witty music circles that fancy themselves as being above commercial networks of the music industry. A strong resistance to political debates is thus a feature of the extreme metal community, which collectively wishes to be something separated from politics. But any metalhead who does not happen to be both male and white isn’t likely to have the luxury of completely separating the music from dynamics of power. The scene is politicized to the bone, albeit in subtle ways, and its opposition to feminity and blackness doesn’t just operate at the ideological and cultural level, but can be sourced in the music itself with its obsession on power and control as well as its rejection of Afro-American musical influences.

Interestingly, I found that my own aesthetic ideals about metal are rooted the idea of music as art devoid of self-reference or representation of reality: a soundscape in which I must be able to forget that I am listening to musicians using amplified instruments. Although I have a limited interest in more obviously escapist themes of paganism, satanism and Lovecraftian mythology, even my seemingly secular taste in metal is dictated by a notion of the autonomous artwork. If something is to be done about these complex dynamics and à prioris, metalheads will have to accept that music doesn’t exist outside of politics, and that it is possible to be both dedicated to extreme metal and critical of it. Only then can we begin to reflect on our own practice and consumption of music. Given that diversification of any given music scene is inevitable anyways, the musical outcome of inclusion can only be enthralling.

Comments

Post a Comment